Since coming back from Christmas, Arthur has been speaking so much more Dutch. Not in a dramatic, overnight way. But slowly. Naturally. Almost quietly. And yet, unmistakably.

We spent a whole week “back home” surrounded by family, playing board games, watching Flemish TV, sharing meals, and chatting about everyday things. There was no structured language practice. No correcting. No pressure. Just life, lived in Dutch.

And something shifted.

Arthur started trying more. Taking more risks. Using longer sentences. Playing with new words. The language began to feel less like something he had to perform and more like something he could simply use.

What surprised me most?

A week after school restarted, it’s still going.

He’s still choosing Dutch music.

Still experimenting with new sentences.

Still bringing Dutch into everyday moments.

From a research perspective, this makes complete sense.

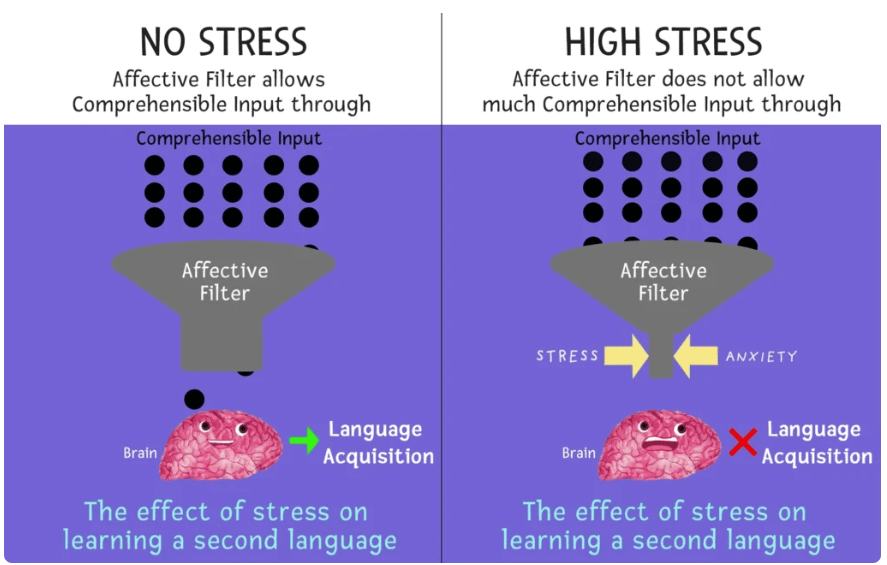

The affective filter matters more than we think

Stephen Krashen’s concept of the affective filter suggests that language acquisition is deeply influenced by emotions. When learners feel anxious, self-conscious, or pressured, their “filter” goes up and acquisition slows. When they feel safe, connected, and relaxed, the filter lowers and language flows in more easily.

Being immersed in Dutch within loving relationships such as grandparents, cousins, aunts and uncles, shared jokes, familiar routines created exactly those low-stress conditions. Arthur wasn’t being evaluated. He belonged. And belonging is a powerful catalyst for language.

Identity drives investment in language

Learners engage more deeply with a language when it feels connected to who they are and who they want to be. This week wasn’t just about increased exposure; it was about identity affirmation.

Dutch wasn’t just a “home language” in theory. It became:

- the language of connection

- the language of play

- the language of family stories

- the language of belonging

No wonder he’s still choosing to engage with it now.

Real input, real interaction, real meaning

Research consistently shows that meaningful, contextualised input is far more powerful than isolated practice. This week provided rich comprehensible input (listening to real conversations, TV, jokes, games) and authentic opportunities for output — but without forced production.

This is exactly the kind of environment where language competence grows naturally.

Not through drills.

Not through worksheets.

Not through correction-heavy practice.

But through lived experience.

So… is it still worth it?

Parents often worry that the minority language is slipping away, especially when children are educated fully in the majority language. That fear is real and understandable. But experiences like this remind us that the minority language is not simply eroding in the background.

It is responsive.

It is relational.

It is deeply connected to emotion, identity, and belonging.

When we nurture those foundations, the language doesn’t just survive. It strengthens.

And yes … it is absolutely still worth it.

Leave a comment